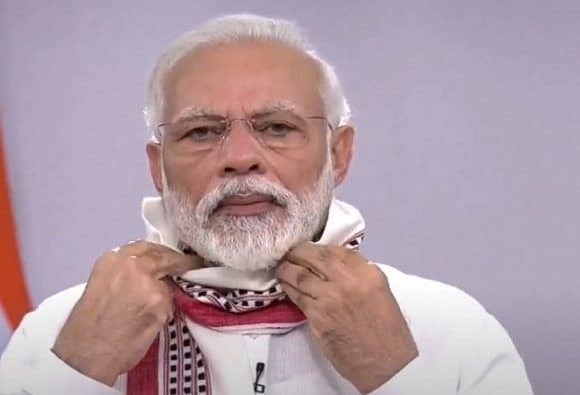

The sprawling camps in Bangladesh housing one million Rohingya refugees from Myanmar are makeshift at best. Bamboo poles, for example, help stabilize flimsy plastic sheeting and tents vulnerable to the heavy rain and strong winds of the monsoon season underway. TRENTON FRANKLIN

This August marks a year since a military crackdown forced at least 700,000 Rohingya to flee Myanmar for Bangladesh, joining hundreds of thousands of Rohingya who had already taken refuge there, totaling 1.1 million people encamped in Cox’s Bazar, according to a Bangladesh count done this July.

But you would never know from the Trump White House about this enormous influx of people escaping from Myanmar to Bangladesh, as President Trump remains mute on the subject. On Capitol Hill, however, a few lawmakers — mostly Democrats — have been spotlighting the horrendous problem.

Unable to safely return to their homes, the Rohingya are packed in sprawling camps in Bangladesh, many living in flimsy tents on tree-stripped hilltops that are vulnerable to wind, flooding and mudslides. Heavy rains early this month signaled the beginning of monsoon season, which typically runs from mid-June through October.

Writing in The Washington Post shortly after visiting with refugees in early July, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres described the atrocities that drove them from their homes in the first place: “Small children butchered in front of their parents. Girls and women gang-raped while family members were tortured and killed. Villages burned to the ground.”

In June, Eric Schwartz, the president of Refugees International, a nonprofit group based in Washington, D.C., told a gathering in the Senate that people fleeing on foot from Myanmar had been gunned down and that Médecins Sans Frontières, or Doctors Without Borders, estimated deaths at upward of 7,000. A recent report by Fortify Rights, a nonprofit human-rights group, based on testimony by survivors and others, supported arguments that Myanmar’s military planned a genocide to rid the country of Rohingya.

But if the mainly Muslim refugees are counting on significant help from Washington, they will be disappointed. President Trump has said nothing about the plight of the Rohingya, never mind responding to charges of ethnic cleansing by Myanmar. Two bills aimed at addressing the crisis never made it to the Senate floor — the majority leadership blocked them.

The administration has made no secret of its disdain for refugee assistance, whether in Bangladesh or in the United States. To fill the State Department’s top position on refugees, it has nominated Ronald Mortensen, a vocal opponent of immigration. Worse, the State Department bureau that manages the refugee flow in the US may soon be closed.

During an observance of World Refugee Day, June 20, the co-chair of the Senate Human Rights Caucus, Chris Coons (D-Delaware), told the audience that he and Senator John McCain (R-Arizona) had urged Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to withdraw Mortensen’s nomination. Fifty-seven Democratic members of the House of Representatives made the same request on July 17. Additionally, human-rights and faith groups have campaigned against his candidacy.

Most recently, rumors circulated that the Trump administration was planning to make the Mortensen nomination moot by shutting the refugee office and shifting policy responsibility on refugees to the White House, which has not been sympathetic to their plight.

Relatedly, in 2017, the White House proposed to eliminate the bureau and transfer its overseas-aid role to Usaid and the refugee work to the Department of Homeland Security. Rex Tillerson, the secretary of state at the time, rejected the plan, but the “future of the bureau absolutely remains under threat given the ongoing reorganization review” of the State Department, said Ann Hollingsworth, a senior policy adviser for Refugees International. She said a recommendation by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo is due imminently.

Moreover, other possible changes may be afoot in the humanitarian aid arena, with the White House proposing, among other reforms, to “improve the efficiency and effectiveness” of the government’s humanitarian assistance across the State Department and Usaid. That includes increasing “burden-sharing” and pushing for reform at the UN regarding such aid.

Refugees International has given the Trump administration an F for failing in its policies and performance regarding refugees.

During the caucus event, Senator Coons noted that Myanmar first stripped the Rohingya of their citizenship in 1982 and has periodically harassed them with military crackdowns. Senator Jeff Merkley (D-Oregon), a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who visited Myanmar and Bangladesh last November, said during the caucus that drawing the world’s attention to the magnitude of the continuing ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya would require an American president to speak up and lead an international response. When he asked if anyone could remember President Trump ever uttering a word about the Rohingya crisis, the room was silent.

In the chaos of the refugee camps, women seem particularly hard hit. Francisca Vigaud-Walsh, a senior advocate for Refugees International, told the caucus about a team visit during which refugees pleaded for protection against gang rape and torture. They pressed for job training for women, many having lost their husbands or other breadwinners.

Help has been slow. Vigaud-Walsh, an expert in gender-based violence, said that some humanitarian organizations found the Bangladeshi government’s registration process so difficult and time-consuming they had to give funds for gender-based violence assistance back to their donors. Groups that were finally registered and funded were unprepared to provide the specialized critical care needed by women who had been sexually assaulted.

Taking the lead on the ground is the UN Refugee Agency, which monitors the Myanmar-Bangladesh border and tries to provide shelter for refugees, especially 6,000 unaccompanied or separated children.

Jana Mason, a senior adviser for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, speaking at the World Refugee Day observance in Washington, praised the Bangladeshi government for opening its borders and noted that since August 2017, the United States has contributed $200 million to the relief effort, through the State Department and Usaid.

That amount is aside from the $951 million urgently needed this year to assist the refugees and their host communities, the UN said in March.

In June, the UN Refugee Agency, the UN Development Program and Myanmar signed an agreement to establish conditions that could enable the refugees to return voluntarily and safely. This would hinge on the UN gaining access to the Rohingya places of origin so they could assess the situation and assure refugees of safe passage and respect for their rights.

Based on a recent visit to the camps with leaders of humanitarian organizations, UN officials concluded that it would be dangerous for refugees to attempt repatriation anytime soon. Bangladesh gave Myanmar a list of 8,032 Rohingya refugees prepared to repatriate, and Myanmar has since cleared about 2,500 of them for return. No one has done so yet. Bangladesh said it would send a delegation to the Burmese capital, Naypyitaw, in August to follow up.

For now, the UN refugee agency has its hands full in the camps. Monsoon season has begun.

Trenton Franklin contributed reporting from Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh; and Stephánie Fillion interviewed Anne Hollingsworth at Refugees International.